“The mouth of the Blackwater Rush had turned into the mouth of hell.”

Synopsis: Along with the rest of Stannis‘ fleet under the command of Ser Imry Florent, Davos Seaworth sails up the Blackwater Rush to his destiny.

SPOILER WARNING: This chapter analysis, and all following, will contain spoilers for all Song of Ice and Fire novels and Game of Thrones episodes. Caveat lector.

Political Analysis:

Davos III, put simply, is the reason George R.R Martin wrote A Clash of Kings the way he did. It is his finest writing in the entire series when it comes to depictions of war – an ordinary man, an uncommon commoner, thrust into a huge setpiece battle with hundreds of ships locked in epic conflict, who sees his sons’ lives snuffed out in an instant, an entire fleet wrecked, and then seems to suffer a horrible death suffering the worst combination of fire and water. No wonder then that Davos III is the only chapter depicting the Battle of Blackwater from Stannis’ side, because how could you top this?

Incidentally, before you read any further, I highly recommend reading BryndenBFish’s Complete Analysis of Stannis Baratheon As a Military Commander, an invaluable resource.

Ser Imry Florent

Continuing the theme of class privilege in warfare that we’ve seen in Davos I and Davos II, in this chapter we learn that command of Stannis’ entire navy, and therefore the success or failure of the whole battle has been placed in the hands of one Ser Imry Florent:

Davos could make out Fury well to the southeast, her sails shimmering golden as they came down, the crowned stag of Baratheon blazoned on the canvas. From her decks Stannis Baratheon had commanded the assault on Dragonstone sixteen years before, but this time he had chosen to ride with his army, trusting Fury and the command of his fleet to his wife’s brother Ser Imry, who’d come over to his cause at Storm’s End with Lord Alester and all the other Florents.

This decision to promote a highborn lord to admiral, seemingly solely on the basis that he’s Selyse’s brother and thus his brother-in-law is Stannis’ major mistake in the Battle of Blackwater, and arguably one of his biggest mistakes in the entire war. Up until the death of Renly, Stannis had generally leaned toward appointing men based on merit rather than rank – hence his preference for Davos over his vassal lords at Dragonstone. But here, Stannis lets himself be influenced by his new vassals (whom he hates) into treating command positions as political favors, which is a major mistake for any would-be monarch. We will see later whether Stannis learns from this mistake, but in the meantime let’s look at the consequences of this decision through an examination of Ser Imry’s tactical decisionmaking:

Ser Imry had decreed that they would enter the river on oars alone, so as not to expose their sails to the scorpions and spitfires on the walls of King’s Landing.

Davos knew Fury as well as he knew his own ships. Above her three hundred oars was a deck given over wholly to scorpions, and topside she mounted catapults fore and aft, large enough to fling barrels of burning pitch. A most formidable ship, and very swift as well, although Ser Imry had packed her bow to stern with armored knights and men-at-arms, at some cost to her speed.

…With four times as many ships as the boy king, Ser Imry saw no need for caution or deceptive tactics. He had organized the fleet into ten lines of battle, each of twenty ships. The first two lines would sweep up the river to engage and destroy Joffrey’s little fleet, or “the boy’s toys” as Ser Imry dubbed them, to the mirth of his lordly captains. Those that followed would land companies of archers and spearmen beneath the city walls, and only then join the fight on the river. The smaller, slower ships to the rear would ferry over the main part of Stannis’s host from the south bank, protected by Salladhor Saan and his Lyseni, who would stand out in the bay in case the Lannisters had other ships hidden up along the coast, poised to sweep down on their rear.

None of these decisions are entirely moronic; in each you can see some military logic at work. But collectively they represent a giant mistake. To begin with, relying entirely on oarpower and loading down his biggest ships means that Ser Imry is choosing defense over speed. It’s a cautious move, arguably hyper-cautious – as we’ll see in a bit, the land-based artillery is nowhere near accurate enough to make the sails a big enough vulnerability to make up for the lost knots – but the consequence is that when the clash between the fleets happens, it’s close enough to the city that Stannis’ crossing “lane” gets turned into a chaotic nightmare of burning ships. Had Ser Imry piled on the sails, the clash would have take place much further up the river, allowing Stannis an open river to get his barges across before the current carried the flaming wreckage toward the boom chain.

In all of his decisions, including his over-all ordering of the fleet which I’ll discuss more in a bit, Ser Imry is focusing on his own battle against the royal navy, and indeed his own glory, rather than his navy’s place in the overall battle – his priority ought to be the crossing of Stannis’ forces, since the major strategic obstacle to victory is the river barrier facing the land forces and the win condition is taking the Red Keep, not whether Ser Imry defeats the royal navy. In which scenario you might have wanted to have the smaller ships meant to carry the troops make a dash for the south bank while the landing parties put their men on the north bank to form a toehold, while keeping himself more in the middle to keep tactical flexibility open and maintain a visual on the whole battlefield. However, in his desire for glory, Ser Imry has designed a naval strategy based on sheer muscle and thus made the classic Salamis error that Stannis as a veteran of the Battle of Fair Isle would never make, more of which in a moment.

Note how the Persian fleet moves from a wide arc formation into a narrowly packed column as the Athenians back water into the straight.

Davos gives us the insight of a veteran sailor, if not a veteran naval officer, looking over the plans of a superior officer put over him by social status rather than ability:

The Onion knight has become an old woman, he could hear them thinking, still a smuggler at heart. Well, the last was true enough, he would make no apologies for it. Seaworth had a lordly ring to it, but down deep he was still Davos of Flea Bottom, coming home to his city on its three high hills. He knew as much of ships and sails and shores as any man in the Seven Kingdoms, and had fought his share of desperate fights sword to sword on a wet deck…

Had he been admiral, he might have done it all differently. For a start, he would have sent a few of his swiftest ships to probe upriver and see what awaited them, instead of smashing in headlong. When he had suggested as much to Ser Imry, the Lord High Captain had thanked him courteously, but his eyes were not as polite. Who is this lowborn craven? those eyes asked. Is he the one who bought his knighthood with an onion?

…Davos was sorry nonetheless. Salladhor Saan was a resourceful old pirate, and his crews were born seamen, fearless in a fight. They were wasted in the rear.

Davos’ suggestions offer us a tantalizing glimpse of an entire alternative strategy for Stannis’ navy. I’ll discuss the ramifications of this strategy extensively in the What If? section, but as you’ll see, throughout this chapter Davos offers a running commentary of the main failures of Ser Imry as a commander. And that’s why Ser Davos Seaworth had to be the POV for this battle. In the very first ASOIAF essay I ever wrote, I said that there have been thousands of Ser Waymar Royces throughout history, brave but stupid aristocrats who’d gotten their men killed because of their fear of looking cowardly or inexperienced. It is also true that there have also been thousands of Davoses, working class non-commissioned officers given orders by men without an ounce of their experience of ability, orders they knew to be stupid and pointless, trapped by the class structure and the chain (ha!) of command, who tried in the midst of clusterfucks, FUBARs, and SNAFUs (it’s not an accident that the common soldier has given us so many words for disasters) to keep their men alive. To hell with the Pattons of history – these men are the real heroes of any war.

At the same time, while there’s much to pick apart between Imry and Davos (and I will), both men are reacting to the inexorable force of GRRM fate:

To be fair, there was reason for Ser Imry’s haste. The winds had not used them kindly on the voyage up from Storm’s End. They had lost two cogs to the rocks of Shipbreaker Bay on the very day they set sail, a poor way to begin. One of the Myrish galleys had foundered in the Straits of Tarth, and a storm had overtaken them as they were entering the Gullet, scattering the fleet across half the narrow sea. All but twelve ships had finally regrouped behind the sheltering spine of Massey’s Hook, in the calmer waters of Blackwater Bay, but not before they had lost considerable time.

Stannis would have reached the Rush days ago. The kingsroad ran from Storm’s End straight to King’s Landing, a much shorter route than by sea, and his host was largely mounted; near twenty thousand knights, light horse, and freeriders, Renly’s unwilling legacy to his brother. They would have made good time, but armored destriers and twelve-foot lances would avail them little against the deep waters of the Blackwater Rush and the high stone walls of the city. Stannis would be camped with his lords on the south bank of the river, doubtless seething with impatience and wondering what Ser Imry had done with his fleet.

This is the critical delay, the reason why I keep harping on about timing in so many chapters. Rather than the simultaneous rendezvous planned by Stannis, his navy arrives after his army despite being able to move many times faster. Now Davos (and by extension GRRM) is somewhat ambiguous about how long this delay actually was, but I would guess that at a minimum we’re talking the loss of one or two days given the way that Davos describes Stannis here. Given that the difference between victory and defeat in the Battle of Backwater can be measured in hours because of the crucial timing of Tywin and the Tyrells’ arrival, it’s safe to say that even half a day lost is devastating for Stannis’ chances.

Nevertheless, as we will see, the battle is not yet lost at this point.

Final Preparations

As the philosopher, Imperial bureaucrat, and dramaturge Seneca once said, luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity. Yes, the storm is hardly helpful, but how Ser Imry responds to it is hugely influential:

The wind was gusting from the south, but under oars it made no matter. They would be sweeping in on the flood tide, but the Lannisters would have the river current to their favor, and the Blackwater Rush flowed strong and swift where it met the sea. The first shock would inevitably favor the foe. We are fools to meet them on the Blackwater, Davos thought. In any encounter on the open sea, their battle lines would envelop the enemy fleet on both flanks, driving them inward to destruction. On the river, though, the numbers and weight of Ser Imry’s ships would count for less. They could not dress more than twenty ships abreast, lest they risk tangling their oars and colliding with each other.

Once again, as with the sails, Ser Imry consistently makes decisions that throw away the advantage of speed, ensuring that the battle will happen relatively far downstream. Thus, rather than having the front lines advance far up the river and give the landing ships a clear space to operate in, they’re going to be tangled up in the action. (To take just a second to talk about pre-modern naval warfare: because ship-to-ship combat in ASOIAF involves either ramming the enemy, preferably head-to-side, or boarding the enemy side-to-side, you tend to get these huge tangled knots of ships that form barriers against free movement in what should otherwise be an open field of battle. On open seas, this tends to be problematic for maintaining formation; on a river or a straight like this, it can be deadly) More consequentially, it means when the fire ships hit, there’s going to be little room for any of the ships behind the first line of battle to maneuver around the chaos before the current of the river pushes the flaming wreckage up against the boom chain, trapping them.

credit to eighthgear

But most importantly, Ser Imry is making one of the classic mistakes of the Battle of Salamis – he’s allowing the terrain to cancel out his advantage of numbers. As Davos notes, the banks of the river eliminates his ability to outflank his enemy and bring pressure to bear at multiple points in the battlefield. In addition, the nature of the battlefield means that the ships behind Ser Imry’s front line can’t bring their weight to bear against the enemy until the ship ahead of them is captured or sunk and opens up a place in the line. In other words, Ser Imry has turned what ought to be an agile and flexible instrument of war into something like the old Greek phalanx, with a front line engaged in a desperate struggle and ranks behind who can only push or step into place when someone in the front line falls. Now, given that he has 200 ships to Tyrion’s 50, Ser Imry can win that kind of battle of attrition, but the danger is that this formation is incredibly inflexible – if anything goes wrong, the ships in the middle can’t move at all, a watery version of the horrible trap that Roman legionaries found themselves in at Cannae.

But numbers alone don’t tell the whole story of Ser Imry’s wrong-headed tactics. Consider also the question of organization and composition:

Fury herself would center the first line of battle, flanked by the Lord Steffon and the Stag of the Sea, each of two hundred oars. On the port and starboard wings were the hundreds: Lady Harra, Brightfish, Laughing Lord, Sea Demon, Horned Honor, Ragged Jenna, Trident Three, Swift Sword, Princess Rhaenys, Dog’s Nose, Sceptre, Faithful, Red Raven, Queen Alysanne, Cat, Courageous, and Dragonsbane. From every stern streamed the fiery heart of the Lord of Light, red and yellow and orange. Behind Davos and his sons came another line of hundreds commanded by knights and lordly captains, and then the smaller, slower Myrish contingent, none dipping more than eighty oars. Farther back would come the sailed ships, carracks and lumbering great cogs, and last of all Salladhor Saan in his proud Valyrian, a towering three-hundred, paced by the rest of his galleys with their distinctive striped hulls. The flamboyant Lyseni princeling had not been pleased to be assigned the rear guard, but it was clear that Ser Imry trusted him no more than Stannis did. Too many complaints, and too much talk of the gold he was owed.

This is military organization as social hierarchy, rather than based on tactical sense. Ser Imry awards himself the place of honor and puts the lords and knights ahead of the sellsails who have more combat experience. Moreover, in his drive to gather the glory for himself and snub people like Davos and Salladhor Saan, he’s ensured that chain of command and tactical flexibility will be lost the moment that Fury encounters the enemy. This is precisely the kind of mistake that Stannis himself would never make, as we’ll see in Tyrion XIII. And as we’ve seen above, it’s also a plan that privileges brute strength above everything else – Ser Imry is putting his heaviest hitters on the front line with the intent to brush aside the enemy (despite the fact that many other factors, from the river itself to his decision to go in with oars alone, limit the effectiveness of this approach), but that also means exposing his strongest assets to enemy fire with little held in reserve. If his 200-oar ships don’t punch through the enemy first line, then he runs the risk of losing them to enemy action or degrading their effectiveness by the time that they come into contact with his enemy’s strongest ships. It also means that his reinforcements will be weaker as the battle goes on, such that his effective fighting strength on the front line will only go down as the battle goes on.

credit to Tomasz Jedruszek

Encountering Tyrion’s Strategy

And it’s at this point that Davos in Black Betha has sailed close enough to the city that he can see Tyrion’s preparation of the battle that’s about to begin:

The squat towers of raw new stone that stood opposite one another at the mouth of the Blackwater might mean nothing to Ser Imry Florent, but to him it was as if two extra fingers had sprouted from his knuckles.

Shading his eyes against the westering sun, he peered at those towers more closely. They were too small to hold much of a garrison. The one on the north bank was built against the bluff with the Red Keep frowning above; its counterpart on the south shore had its footing in the water. They dug a cut through the bank, he knew at once. That would make the tower very difficult to assault; attackers would need to wade through the water or bridge the little channel. Stannis had posted bowmen below, to fire up at the defenders whenever one was rash enough to lift his head above the ramparts, but otherwise had not troubled.

Something flashed down low where the dark water swirled around the base of the tower. It was sunlight on steel, and it told Davos Seaworth all he needed to know. A chain boom…and yet they have not closed the river against us. Why?

…As the second line swept past the twin towers, Davos took a closer look. He could see three links of a huge chain snaking out from a hole no bigger than a man’s head and disappearing under the water. The towers had a single door, set a good twenty feet off the ground. Bowmen on the roof of the northern tower were firing down at Prayer and Devotion. The archers on Devotion fired back, and Davos heard a man scream as the arrows found him.

I absolutely love how GRRM does this. Davos is too experienced a sailor, and a King’s Landing native to boot, not to notice Tyrion’s boom chain and know that it’s a trap. However, Davos can only see the second half of the trap (the first being the wildfire), and doesn’t understand why the boom chain isn’t being used conventionally. In this fashion, the first time reader sees what Tyrion’s chain has been about, but doesn’t yet understand its purpose until GRRM is ready to reveal his hand. And his attention to detail is impressive – the towers that protect the winching mechanisms have been situated relative to the geography to make them almost impossible to take, especially the tower on the south bank with its own moat. (More on this in the What If? section)

And as both the fleet and the chapter moves on, we now see how Tyrion has shaped his tactics around his two technical innovations. Far too many times in history, commanders have failed to adapt their tactics to new technologies – the generals of the Civil War who used Napoleonic infantry tactics when rifling and breech-loading weapons made them a recipe for murder, the commanders during WWI who completely failed to understand the power of machines and barbed wire, and on and on. But Tyrion is too good a commander to make that mistake:

The river that had seemed so narrow from a distance now stretched wide as a sea, but the city had grown gigantic as well. Glowering down from Aegon’s High Hill, the Red Keep commanded the approaches. Its iron-crowned battlements, massive towers, and thick red walls gave it the aspect of a ferocious beast hunched above river and streets. The bluffs on which it crouched were steep and rocky, spotted with lichen and gnarled thorny trees. The fleet would have to pass below the castle to reach the harbor and city beyond.

The first line was in the river now, but the enemy galleys were backing water. They mean to draw us in. They want us jammed close, constricted, no way to sweep around their flanks…and with that boom behind us. He paced his deck, craning his neck for a better look at Joffrey’s fleet. The boy’s toys included the ponderous Godsgrace, he saw, the old slow Prince Aemon, the Lady of Silk and her sister Lady’s Shame, Wildwind, Kingslander, White Hart, Lance, Seaflower. But where was the Lionstar? Where was the beautiful Lady Lyanna that King Robert had named in honor of the maid he’d loved and lost? And where was King Robert’s Hammer? She was the largest war galley in the royal fleet, four hundred oars, the only warship the boy king owned capable of overmatching Fury. By rights she should have formed the heart of any defense.

Davos tasted a trap, yet he saw no sign of any foes sweeping in behind them, only the great fleet of Stannis Baratheon in their ordered ranks, stretching back to the watery horizon. Will they raise the chain and cut us in two? He could not see what good that would serve. The ships left out in the bay could still land men north of the city; a slower crossing, but safer.

Here, Tyrion has arranged both the geography, his technology, and his navy to put Stannis’ navy in a trap, and get as close to the ideal of the double-envelopment (note, for example the way his fleet deliberately retreats, as per the Greek fleet at Salamis) as he can get with an inferior navy, by using the wildfire and the boom chain to compensate for the lack of a second fleet that could attack from behind as Davos expects. Rather than simply barring Stannis’ fleet from the river (which might work in the short-term but wouldn’t stop a northern landing and would eventually be thwarted by a determined assault on the southern tower), or even dividing Stannis’ fleet so that he can face them on even terms (which only gets his odds to 50-50), Tyrion reaches for total victory by crushing Stannis’ fleet entirely. And to accomplish this, he’s willing to sacrifice most of his own navy to get Ser Imry to fully commit to his attack – we have nine ships named here, but as we’ll see in Tyrion XIII and again in AFFC, the final butcher’s bill will come in much higher.

One question that does come to mind, and I’ll discuss this more in the What If? section, is why Stannis’ men didn’t attempt the landing north of the city that Davos suggested. After all, even in the OTL scenario where Ser Imry fully commits to the attack, Salladhor Saan’s ships remain on the far side of the chain, and could have shuttled men over to the north bank. This may come down to a communications failure, but it would seem a better large-scale solution than the burning ship bridge.

Symbolic Politics

And then…we take a brief break for a discussion of the internal politics of the Stannis Baratheon coalition, in which we see that Davos, well before he’s even been discussed as a potential Hand of the King, has some good political instincts:

South of the Blackwater, Davos saw men dragging crude rafts toward the water while ranks and columns formed up beneath a thousand streaming banners. The fiery heart was everywhere, though the tiny black stag imprisoned in the flames was too small to make out. We should be flying the crowned stag, he thought. The stag was King Robert’s sigil, the city would rejoice to see it. This stranger’s standard serves only to set men against us.

He could not behold the fiery heart without thinking of the shadow Melisandre had birthed in the gloom beneath Storm’s End. At least we fight this battle in the light, with the weapons of honest men, he told himself. The red woman and her dark children would have no part of it. Stannis had shipped her back to Dragonstone with his bastard nephew Edric Storm. His captains and bannermen had insisted that a battlefield was no place for a woman. Only the queen’s men had dissented, and then not loudly. All the same, the king had been on the point of refusing them until Lord Bryce Caron said, “Your Grace, if the sorceress is with us, afterward men will say it was her victory, not yours. They will say you owe your crown to her spells.” That had turned the tide. Davos himself had held his tongue during the arguments, but if truth be told, he had not been sad to see the back of her. He wanted no part of Melisandre or her god.

Before I get into the politics, let me note that these rafts are a big part of the reason why I consider Ser Imry’s decisions that slowed the pace of the fleet to be a mistake – because the further up-river the clash between the two fleets happens, the more time these rafts have to actually cross the Blackwater and make an impact on the north bank. With Ser Imry’s strategy, the conflict seems to have prevented these rafts from being used – hence the boat bridge.

With that out of the way, I have to agree with Davos that Stannis’ adoption of the flaming heart banner missed an opportunity to win hearts and minds – as we’ve seen throughout ACOK, the current regime in King’s Landing is widely perceived as a Lannister monopoly, and Stannis’ claims are widely believed. Presenting himself as the indisputable choice of Baratheon loyalists by flaying the traditional banner could have helped in the struggle to win hearts and minds. But while the decision to change the banners suggests that Stannis has been “captured” by the R’hlloric forces within his coalition, the quote above shows that the political situation has become more complicated since he took charge of Renly’s cavalry. Stannis is now trying to lead a large number of lords who weren’t present for any of the political groundwork that created the Queen’s Men faction, and who may well believe that Melisandre’s magic killed the king they had been following up until recently. Moreover, we can see that in addition to the class prejudice that Davos faces, there’s an unhealthy amount of misogyny, xenophobia, and religious bigotry among the assembled lords of the Stormlands and the Reach.

And this lends itself to another What If? that I’ll discuss later – Melisandre is fully capable of working weather magic to guide a fleet swiftly and safely across the waters, as we see in retrospective in ASOS, potentially butterflying away the effects of the storm. Moreover, Melisandre has some fire magic (although how extensive we don’t know yet) and obliquely claims in ASOS that she could have changed the outcome of the Battle of Blackwater with regard to the wildfire.

The First Landings Foiled

Another sign that things aren’t going well for Team Stannis is that, rather than successfully seizing a foothold on the north bank , they’re being pushed back:

To starboard, Devotion drove toward shore, sliding out a plank. Archers scrambled into the shallows, holding their bows high over their heads to keep the strings dry. They splashed ashore on the narrow strand beneath the bluffs. Rocks came bouncing down from the castle to crash among them, and arrows and spears as well, but the angle was steep and the missiles seemed to do little damage.

Prayer landed two dozen yards upstream and Piety was slanting toward the bank when the defenders came pounding down the riverside, the hooves of their warhorses sending up gouts of water from the shallows. The knights fell among the archers like wolves among chickens, driving them back toward the ships and into the river before most could notch an arrow. Men-at-arms rushed to defend them with spear and axe, and in three heartbeats the scene had turned to blood-soaked chaos. Davos recognized the dog’s-head helm of the Hound. A white cloak streamed from his shoulders as he rode his horse up the plank onto the deck of Prayer, hacking down anyone who blundered within reach.

Three ships out of a fleet of 200 making an isolated landing, without support from the dozens of warships that are passing them, points to a lack of attention being paid by Ser Imry to an absolutely vital part of the battle. These transport ships should be landing in concerted waves of dozens of ships so that they can land enough men to hold out rather than get pushed back into the water, and they should be at the very least getting fire support from the heavy warships to disrupt and weaken the sortie parties. Likewise, Ser Imry seems to have botched the organization of the landing parties, such that the archers are first off the boat where they can be cut to pieces by Sandor Clegane’s cavalry charges*, while the dismounted men-at-arms with their polearms and plate armor are in the second wave, unable to render assistance.

* A quick side-note: I love the little detail that shows what a ridiculous badass Sandor Clegane is during the early stages of the Battle of Blackwater, because of the way in which his resigning in Tyrion XIII turns into a legend of his cowardice in ASOS and AFFC. As with Podrick Payne, the true heroes of the Battle of Blackwater go unremembered, even as those who sucker-punched a smaller army get the laurels. Sandor riding his horse up onto the deck of the Prayer is bizarrely reminiscent of Gregor; both Clegane brothers have a tendency to do ridiculous feats of equestrianism.

Reverse these two lines and Sandor’s sortie (and Tyrion’s, for that matter) would likely bounce off the disciplined lines of the men-at-arms – historically speaking, dismounted men-at-arms were ferociously good defensive troops, and absolutely crucial to English strategy at Crecy, Poiters, and Agincourt, holding the line against the French chivalry and protecting the lightly-armored archers – while the archers safely disembarked and formed up into disciplined ranks that could provide effective volley fire. The fact that all of this is completely backwards suggests that Ser Imry completely neglected his primary mission in favor of focusing on winning glory through a head-to-head clash with the royal navy. If he had survived the Battle of Blackwater, win or lose, I would have recommended he join his uncle in front of a firing squad, pour encourager les autres.

Moreover, once Davos pulls into sight of the riverfront, he sees that Tyrion’s preparations have paid off in further slowing down Stannis’ progress:

Beyond the castle, King’s Landing rose on its hills behind the encircling walls. The riverfront was a blackened desolation; the Lannisters had burned everything and pulled back within the Mud Gate. The charred spars of sunken hulks sat in the shallows, forbidding access to the long stone quays. We shall have no landing there.

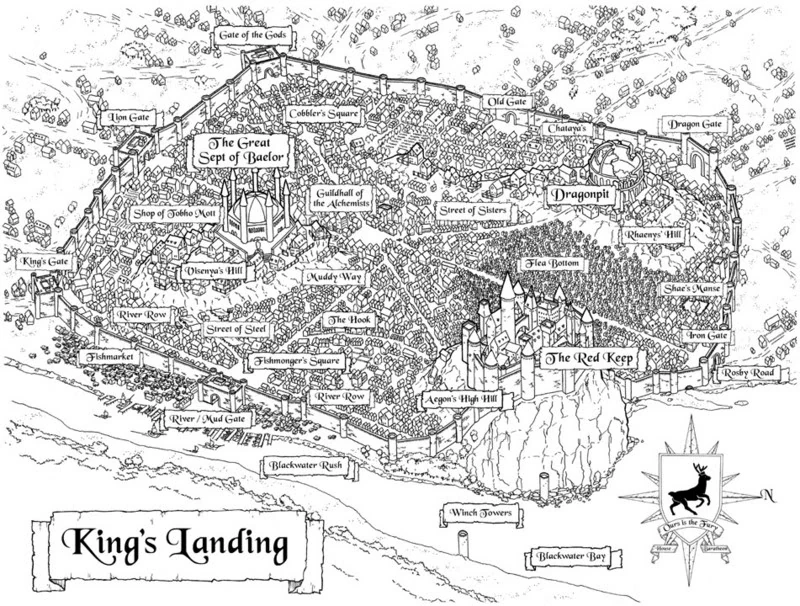

Even more than burning the riverfront, this shows the extent of Tyrion’s commitment to scorched-earth tactics. The riverfront is the heart of King’s Landing’s economy and sinking hulks in front of the quays basically eliminates the harbor as a viable destination for commerce, as Tyrion finds out when he becomes Master of Coin in ASOS and gets tasked with fixing the damage that the Battle of Blackwater caused. At the same time, however, you can definitely see how necessary that was for impeding Stannis’ landings if you look at a map:

The quays are right in front of the Mud Gate; if Stannis’ ships can directly disembark rather than having to beach either upstream or downstream, then they can attack the gate immediately and it becomes much more difficult for Tyrion to disrupt them on the beaches with his sortie parties. In this case, unlike so many cases in history, military necessity really does require their sacrifice.

The Fleets Clash

Now that the preliminaries are over, the Battle of Blackwater moves into a new phase as the two fleets clash. In this scene, GRRM finally gets to let his inner Patrick O’Brien fanboy loose and give us the full spectacle of naval combat that we never got to see in the show:

Davos never saw the battle joined, but he heard it; a great rending crash as two galleys came together. He could not say which two. Another impact echoed over the water an instant later, and then a third. Beneath the screech of splintering wood, he heard the deep thrum-thump of the Fury’s fore catapult. Stag of the Sea split one of Joffrey’s galleys clean in two, but Dog’s Nose was afire and Queen Alysanne was locked between Lady of Silk and Lady’s Shame, her crew fighting the boarders rail-to-rail.

Directly ahead, Davos saw the enemy’s Kingslander drive between Faithful and Sceptre. The former slid her starboard oars out of the way before impact, but Sceptre’s portside oars snapped like so much kindling as Kingslander raked along her side. “Loose,” Davos commanded, and his bowmen sent a withering rain of shafts across the water. He saw Kingslander’s captain fall, and tried to recall the man’s name.

Ashore, the arms of the great trebuchets rose one, two, three, and a hundred stones climbed high into the yellow sky. Each one was as large as a man’s head; when they fell they sent up great gouts of water, smashed through oak planking, and turned living men into bone and pulp and gristle. All across the river the first line was engaged. Grappling hooks were flung out, iron rams crashed through wooden hulls, boarders swarmed, flights of arrows whispered through each other in the drifting smoke, and men died…but so far, none of his.

Black Betha swept upriver, the sound of her oarmaster’s drum thundering in her captain’s head as he looked for a likely victim for her ram. The beleaguered Queen Alysanne was trapped between two Lannister warships, the three made fast by hooks and lines.

“Ramming speed!” Davos shouted.

The moment the front lines engage, the panoramic view that Davos has been giving us disappears into a chaotic, intimate depiction of pre-blackpowder naval combat. It’s said that the person who understands a battle least is the ordinary soldier, because their perspective is shrouded by the fog of war and distorted by the intense emotion and shock of near-death, and we certainly get that here. All of which makes it an even worse idea for the flagship to be dead-center in the first line of battle, because the moment that Fury is locked in conflict, Ser Imry ceases to be able to command his fleet just as surely as if he’d died in the opening exchange.

By contrast, Davos’ instincts are always to act in defense of others – focusing fire at the Kingslander’s captain to disrupt his attack on the Faithful and the Sceptre, and then ramming Lady’s Shame to protect the Queen Alysanne from being boarded. In part this is driven by his awareness that his son Dale is commanding the Wraith, Allard the Lady Marya, and Maric is serving on the Fury, given him a very personal stake in the well-being of his fellow sailors. But I think no small part of it is that Davos can identify with the common soldier in a way that highborn commanders simply don’t, seeing the human being rather than a game piece on a giant board of cyvasse.

Smoke on the Water, Fire in the Sky

If you thought the normal experience of pre-blackpowder ship-to-ship combat was chaotic, things get even worse when wildfire enters the fray:

A flash of green caught his eye, ahead and off to port, and a nest of writhing emerald serpents rose burning and hissing from the stern of Queen Alysanne. An instant later Davos heard the dread cry of “Wildfire!”

He grimaced. Burning pitch was one thing, wildfire quite another. Evil stuff, and well-nigh unquenchable. Smother it under a cloak and the cloak took fire; slap at a fleck of it with your palm and your hand was aflame. “Piss on wildfire and your cock burns off,” old seamen liked to say. Still, Ser Imry had warned them to expect a taste of the alchemists’ vile substance. Fortunately, there were few true pyromancers left. They will soon run out, Ser Imry had assured them.

…the fire was spreading over Queen Alysanne and her foes faster than he would have believed possible. Men wreathed in green flame leapt into the water, shrieking like nothing human. On the walls of King’s Landing, spitfires were belching death…

…For those few instants, Black Betha and White Hart were the calm eye in the midst of the storm. Queen Alysanne and Lady of Silk, still locked together, were a ranging green inferno, drifting downriver and dragging pieces of Lady’s Shame. One of the Myrish galleys had slammed into them and was now afire as well. Cat was taking on men from the fast-sinking Courageous. The captain of Dragonsbane had driven her between two quays, ripping out her bottom; her crew poured ashore with the archers and men-at-arms to join the assault on the walls. Red Raven, rammed, was slowly listing. Stag of the Sea was fighting fires and boarders both, but the fiery heart had been raised over Joffrey’s Loyal Man. Fury, her proud bow smashed in by a boulder, was engaged with Godsgrace. He saw Lord Velaryon’s Pride of Driftmark crash between two Lannister river runners, overturning one and lighting the other up with fire arrows. On the south bank, knights were leading their mounts aboard the cogs, and some of the smaller galleys were already making their way across, laden with men-at-arms. They had to thread cautiously between sinking ships and patches of drifting wildfire. The whole of King Stannis’s fleet was in the river now, save for Salladhor Saan’s Lyseni. Soon enough they would control the Blackwater. Ser Imry will have his victory, Davos thought, and Stannis will bring his host across, but gods be good, the cost of this…

I love how GRRM handles the use of wildfire here, because he fakes both Ser Imry and the reader into thinking that Tyrion et al. are going to use “the substance” in a conventional fashion. Even at a conventional level, wildfire is appropriately terrifying, as we see four ships made of wood and rope and canvas and caulked with tar go up like torches lit by an unquenchable fire. At the same time, through the chaos we can see that Stannis’ navy is winning by sheer force – the river is under Stannis’ control, Dragonsbane has landed men at the quays, and Stannis’ men on the south bank are beginning to make their crossing. But as Davos points out, Ser Imry clearly learned his tactics at the Ronald Rust School of War (a battle is a glorious victory if you can subtract your casualties from the casualties of the enemy and come up with a positive number).

And it’s at this hopeful moment for Stannis’ side, when it looks like their sacrifice might have bought them victory, the battle takes a sudden turn. GRRM slow-rolls the reveal of the fire ships like a horror movie showing their monster bit by bit so as not to peak too early:

Through black smoke and swirling green fire, Davos glimpsed a swarm of small boats bearing downriver: a confusion of ferries and wherries, barges, skiffs, rowboats, and hulks that looked too rotten to float. It stank of desperation; such driftwood could not turn the tide of a fight, only get in the way. The lines of battle were hopelessly ensnarled, he saw.

…It was Swordfish, her two banks of oars lifting and falling. She had never brought down her sails, and some burning pitch had caught in her rigging. The flames spread as Davos watched, creeping out over ropes and sails until she trailed a head of yellow flame. Her ungainly iron ram, fashioned after the likeness of the fish from which she took her name, parted the surface of the river before her. Directly ahead, drifting toward her and swinging around to present a tempting plump target, was one of the Lannister hulks, floating low in the water. Slow green blood was leaking out between her boards.

When he saw that, Davos Seaworth’s heart stopped beating…

What comes next is an entirely different kind of warfare, so far removed from the ordinary experience of medieval combat that I don’t think anyone who experienced it at ground level really comprehends what’s going on. These moments when the entire order of things is overturned come rarely in military history – Cynocephalae, Crécy, Shiloh, the clash of the Monitor and the Merrimack, the machine guns and poison gas at Ypres, the Blitzkreig, and Hiroshima – and while the military historian might, with hindsight, speak confidently of revolutions placed in the context of long-term changes in technology and organization, for the common soldier it is a bewildering, irrational, and unjust crime against nature. And so for Davos, the firebombs on the water can only be explained as an apocalypse:

Then he heard a short sharp woof, as if someone had blown in his ear. Half a heartbeat later came the roar. The deck vanished beneath him, and black water smashed him across the face, filling his nose and mouth. He was choking, drowning. Unsure which way was up, Davos wrestled the river in blind panic until suddenly he broke the surface. He spat out water, sucked in air, grabbed hold of the nearest chunk of debris, and held on.

Swordfish and the hulk were gone, blackened bodies were floating downstream beside him, and choking men clinging to bits of smoking wood. Fifty feet high, a swirling demon of green flame danced upon the river. It had a dozen hands, in each a whip, and whatever they touched burst into fire. He saw Black Betha burning, and White Hart and Loyal Man to either side. Piety, Cat, Courageous, Sceptre, Red Raven, Harridan, Faithful, Fury, they had all gone up, Kingslander and Godsgrace as well, the demon was eating his own. Lord Velaryon’s shining Pride of Driftmark was trying to turn, but the demon ran a lazy green finger across her silvery oars and they flared up like so many tapers. For an instant she seemed to be stroking the river with two banks of long bright torches.

It’s some of the best writing that GRRM has ever done, and I defy anyone not to feel for Davos as he sees Stannis’ fleet, his own ship, and his four sons burn in one horrible instant. And for Davos, this is where his Battle of Blackwater ends, without even the time to mourn as he is “being swept out into the bay,” fighting the current and the “burning spars and burning men and pieces of broken ships” fouling the water. And then, just when survival seems possible once again, he sees “…the chain. Gods save us, they’ve raised the chain.“

Tyrion’s masterstroke is complete, both parts of the trap are sprung. May the gods forgive him for it.

Historical Analysis:

With the Second Arab Siege, the similarities between Constantinople and King’s Landing swim into sharper focus. In 717 CE, the Umayyid Caliph Sulayman believed that he was on the verge of a millenial victory over the Byzantines, thanks to a prophecy that the city would fall to a caliph with the name of a prophet. The Byzantines, meanwhile, had been in an extended period of civil war and anarchy following the overthrow of Justinian II in 711. Sulayman assembled a massive army of 120,000 men and 1,800 ships to completely surround the city, learning the lessons from the First Arab Siege of a generation earlier.

Just to make certainty double certain, Sulayman even intervened in the Byzantine civil war, backing Leo the Isaurian against Theodosius III. Unfortunately for the Caliph, the new Emperor Leo III proved to be both wily and completely untrustworthy and, after promising to make Constantinople a vassal state of the Caliphate, promptly double-crossed his putative masters and fortified the city against them the moment he was crowned. Similar to Tyrion (and indeed to Brynden Tully in defense of Riverrun), Leo III embraced scorched-earth tactics to denude the countryside of supplies and evacuated every resident of Constantinople who lacked a three-year supply of food.

Enraged, Sulayman conducted an elaborate operation to cut off the city and starve it to death. (Reportedly, at one point Leo III offered to buy him off with a gold piece per resident of Constantinople and was turned down) Shielded by their enormous fleet, Arab forces crossed over to Thrace to besiege the city from the land side, where they built enormous double walls to prevent any supplies from getting in from that direction or reinforcements from relieving the city. While another Arab army held the Asia Minor side of the Bosphorus, Sulayman sent his navy into the channel to cut the city off from the Black Sea.

It was at this moment where Leo III acted, sending out his smaller navy to assault the rearguard of the Arab fleet. Turning once again to the Greek Fire that had served them in the previous Arab siege, the Byzantine fleet burned 20 ships carrying some 2,000 men then and there. When the Arab fleet pursued, Leo III had the boom chain raised, sheltering his ships in the safety of the Golden Horn while the Arab fleet looked on helplessly. And so it went all that winter, as the two navies exchanged hit-and-run blows as the Arabs sought to cut off the city from supplies and the Byzantines retaliated where they could, each time retreating behind the safety of the great chain while the Arab fleets were left to contend with the treacherous Sea of Marmora. Meanwhile, Leo III and Sulayman engaged in a bitter battle of diplomacy and logistics, much like Tywin’s war of quills and ravens.

In this test of endurance, the sheer size of the Arab armies worked against them – slowly, they began to run out of food, and in the wake of famine came plague and reports of cannibalism. At this critical moment, Sulayman died and his successor ordered two fleets (one from Egypt, which is important for reasons that will be explained shortly) with a combined 760 ships to bring supplies to his beleaguered armies in the spring. Alerted by his spies in Egypt, Leo III decided to go all in and sent his entire navy to wipe out the supply fleets, armed with Greek Fire.

At the very moment when the Byzantine navy attacked, the Egyptian fleet’s crew, which was largely made up of Coptic Christians, promptly defected. Betrayed and burning, the supply fleets went to the bottom of the Sea of Marmora. Starving and losing hope, the Arab armies were now vulnerable – the Bulgars, loaded down with promises of Byzantine gold, attacked the Arab forces on the Thracian side, while a Byzantine army ambushed and destroyed a relief army marching north on the Asiatic side. Finally, with no other options, the order was given to retreat.

And then something amazing happened. As the Arab fleet sailed south, a huge storm swept south through the Sea of Marmora, wrecking ships left and right. And if that wasn’t bad enough, an active volcano on the Aegean started setting ships on fire with clouds of embers and ash. The great Arab fleet was no more. (According to Byzantine propaganda, only five ships out of 1,800 made it back; according to Arab propaganda, as many as 150,000 soldiers died in combat or of disease, starvation, or cannibalism.) And all of this happened on the eve of the Assumption of Mary, a clear sign to the jubilant Byzantines that, once again, God had defended his chosen city.

But lest you leave this chapter thinking that Greek Fire is uncomplicatedly awesome, let me explain why I empathize so much with Davos in this chapter. The dapper gent pictured above is my grandfather, Reginald “Reg” Attewell. In 1940, he was a soldier in the Royal Engineers, building railroad infrastructure in France to support the British Expeditionary Force and their French allies. As one of the few members of his unit who spoke French, Reg was manning the radio when the news came across the wireless that the German blitzkrieg had broken through in the Ardennes.

His unit was withdrawn to St. Nazaire, where they were boarded on to the RMS Lancastria, which is a name you might be familiar with if you’re a student of famous naval disasters. A former ocean liner pressed into service for the Dunkirk evacuations weeks earlier, the Lancastria was stuffed full of anywhere from four to nine thousand British military and civilian refugees as it waited to depart on June 17th, and Reg was one of them. At 3:48 in the afternoon, the Lancastria was hit by a Junker Ju88 bomber and began to sink.

Because of the overcrowding of the ship, the crew had put chains on some of the doors to the hold to keep passengers from coming up on deck and crowding the walkways. As the ship began to list, Reg climbed his way up the stairs to one of these doors only to find it chained shut – and so he had to climb all the way back down into the hold to find another exit that wasn’t chained up, and then climbed all the way up again. If you want to understand the chaos and urgency of the moment, remember that from the beginning of the attack to the ship going under for the last time, the sinking of the Lancastria took only 20 minutes.

One of the things that made shipwrecks in WWII especially dangerous was that ships of that era were oil-powered, so when they were hit badly as the Lancastria was, the oil leaked. And in this case, 1,400 tons of fuel poured into the waters, turning into a vast shimmering slickness. And the problem with oil is that, when you shoot it with a tracer round, as the Junkers did, it catches fire.

So Reg, having climbed his way out of a sinking ship twice, now had to swim underwater as the waves burned above him, holding his hands over his face when he came up for air to shield it from the fire (scarring the back of his hands permanently), until he could reach an evacuation ship. My grandfather was one of 2,447 survivors of the sinking of the RMS Lancastria, the greatest naval disaster in British history. Like Davos, he was one of the lucky ones. And like Davos, he would go on to fight again, while experiencing miraculous escapes time and again – reassigned to the Asian Theatre, Reg managed to get himself on one of the last British ships to get out of Singapore before the city fell to the Japanese in 1941, and spent the rest of WWII alternately building and then blowing up railroad bridges in Burma and India (which involved transporting cases of leaky dynamite on the back of military jeeps built without suspension on dirt roads in the heat of summer).

So whenever I read Davos, I think of Reg.

What If?

As you might imagine in a battle of this complexity, there’s an enormous scope for hypotheticals. I’ve picked out a few choice ones for your enjoyment:

- Davos in charge? If Stannis had discovered his gumption a half book earlier and appointed Davos to be his Hand of the King, the Battle of Blackwater would have been radically different. Now, Davos doesn’t tell us the whole of his strategy, but he does say that “he would have sent a few of his swiftest ships to probe upriver and see what awaited them, instead of smashing in headlong.” Now it’s possible that these fast ships could have tripped the wildfire trip all by themselves, but at the very least this would have meant that Davos would have began the battle knowing about the boom chain and that Tyrion’s navy wasn’t seriously contesting the river.

- Along with going in under sails and oars both, this may well have meant that Davos pivots strategy from a frontal assault aimed at the enemy navy to a landing-based strategy that prioritizes getting in and out quick, as befits his background as a smuggler. At the very least, Stannis’ fleet absorbs fewer casualties – meaning win or lose, he’s going to have a navy that could stand up to the Redwynes. And if Stannis can get even the narrowest window to cross the river, this changes the battle entirely: the Tyrells’ attack is completely negated, the city will fall easily, and he can then turn his entire 21,000-man army against Tywin’s slightly outnumbered and outmatched (keep in mind, Stannis has 16,000 cavalry to Tywin’s 7,000) force.

- Stannis’ men attack the southern tower? One of the things I’ve always wondered is why Stannis’ army, given that they were on-site for days ahead of the navy, didn’t attack the southern boom-chain tower. Yes, there would be a substantial number of casualties, given how well-built the tower is, but the boom chain would be rendered ineffective. Yes, that means no boat bridge, but it also means that much of Stannis’ fleet could have backed-water out of the river and out of the way, let the burning wreckage pass out into the bay, and then sail back in with Salladhor Saan’s ships as backup. This would take some time, and this battle is incredibly time-sensitive so it might have been fruitless, but with a completely open river, Stannis’ entire army could have made the trip. Finally, Stannis’ navy remains largely intact, which means win or lose, Stannis can maintain naval parity even with the Redwynes present.

- Stannis’ landing men do the landing north of the city? This is an interesting alternative strategy, because it completely bypasses all of Tyrion’s preparations. The 5,000 men on the landing ships could obviously attack the city hours ahead of the 16,000 on the south bank who would have to trans-ship, but given that the overwhelming majority of the Goldcloaks are deployed on the city’s southern walls, they might very well have been able to storm the undefended north side and take the panicky defenders in the rear as the force on the south bank acts as a distraction. On the other hand, if Stannis just takes the time to move his whole army over, there’s not really anything that Tyrion can do to stop him.

- Melisandre was present for the battle? To me, this is the wildest potential hypothetical. Assuming for the sake of argument that Melisandre can back up her boasts, this would essentially play as per Ser Imry’s plan with two main difference. First, the storm is butterflied away, so the battle begins at least a day earlier, so Tywin and the Tyrells are way too far away to ride in to save the day. But second, a genuine damn miracle is manifest on the waters of the Rush as the hand of R’hllor spares Stannis’ navy. Not only would Stannis win a stunning victory, but I’m pretty sure that, at the very least 21,000 men convert to the worship of the Red God, because visual evidence of the divine is pretty compelling.

Book vs. Show:

I will say right now that Neil Marshall deserves undying respect for what he was able to accomplish on an $8 million budget, with most of the group shots done in a quarry like a glorified episode of old-school Doctor Who. Yes, we didn’t get the chain or the huge naval combat, but the one fire ship is an elegant refinement of the basic premise. And I’m quite astonished at how he was able to suggest a city and its defenders, and an entire navy and army, with 250 extras, one (ONE!) full-sized ship, and 13 horses.

My only critique about this sequence, and this has nothing to do with Neil Marshall and everything to do with earlier script decisions, is that Davos being in charge at this moment does strange things to his and Stannis’ arc in Season 3. In the books, we have a clear arc – Davos goes from being a marooned sailor on the verge of death to a prisoner in the dungeons to the Hand of the King; Stannis triumphs over his depression, wrestles with his conscience, and learns to be his own man as King. But if Davos is commanding the fleet in Season 2, then technically the loss of the battle is his fault (on the “buck stops here” principle), and his promotion to Hand of the King is oddly weightless without the comparison to the faithless aristocrat Alester Florent (who still dies, for no reason now, in Season 4).

It’s weird to remember that there are only three Davos chapters in ACOK.

Honestly, I find the critiques of Florent pretty heavily influenced by knowledge of later events. Based on the information he had, there was nothing wrong with any of his tactics, and some of Davos’ suggestions don’t really make sense. We’re told outright that the first line of Tyrion’s ships is blocking the river, so there’s no possibility of scouting up the river, which in any event wouldn’t matter unless his men can X-ray vision the hulls of the ships further up. The boom chain being lowered is somewhat odd, but the real fault there is Stannis’ for not attacking it; Florent’s priority is to secure control of the river and facilitate Stannis’ crossing. And naval technology in this era is pretty heavily favoured toward the bigger ship, so sending his smaller ships in as fodder for the bigger ones (which is what they’d be, no matter that their sailors are more experienced) doesn’t make much sense.

Florent secures a victory over Tyrion’s conventional naval forces, pretty easily. It’s what he doesn’t know that screws him, and there was no way he could have prepared for that.

There is a certain amount of presentism, but I do think there is a strong case that Florent put the priority on winning the naval battle over an effective landing.

And I dispute that Tyrion’s ships were effectively blocking the river up to the mouth – when Davos and co sail in there’s a long period where he doesn’t see the opposition, the enemy backs-water rather than rushes in, much of Tyrion’s navy is hidden way up-stream, etc.

And what would they see, these scouts that Davos wants to send? Only Tyrion’s warships. Unless you’re going to throw away a few ships completely needlessly into the teeth of a locally superior force, in which case the whole purpose of scouting is rendered moot.

And how would they report? There are no radios, there are no signaling flags (and if there were it’s too dark for them to be used). The only way for a scout to report would be to turn around, dock with Fury or send a boat, personally report to Ser Imry Florent, stopping the entire fleet in the meantime to keep formation. You want to talk about unnecessary delays? There’s one for you right there.

I am entirely with Sean C on this. Imry Florent comes out of this looking like a fool entirely, completely, because of matters beyond his control. He is the definition of “scapegoat who is conveniently dead”.

He anticipated wildfire might be used and took what precautions he could against it. He had no way of anticipating that halfway across the planet a teenage girl had succeeded in hatching dragons, leading to a massive worldwide strengthening of fire magic, allowing the pyromancers to quintuple wildfire output.

He had no way to anticipate that Stannis’s scouts, many of whom are stormlanders who ought to be intimately familiar with the kingswood, manage to get killed to a man by barbarians from the Mountains of the Moon (which is completely ridiculous and such an utter fail that I’m surprised that it’s so accepted amongst the fandom).

He had no way to anticipate that Stannis would allow a brand new, very suspicious structure sitting right next to him to go completely unmolested for days.

He had no way to anticipate that Tywin and the Tyrells were that close- neither of them should have been anywhere near given the best information he had. Therefore, he had all the time in the world, or at least thought he did.

Bottom line, Imry Florent’s job was to secure the Blackwater Rush for Stannis. He did that. No landing can be successful while there are enemy naval forces to oppose it. He removed them.

And while I’m at it, your criticism of lowering the sails and proceeding only on oars is also wrong. Sails are only useful when you have the wind at your back or you can maneuver (tack) to get the wind.

There’s a reason pre-blackpowder navies that relied on ramming always lowered the sails before battle; indeed, the Ancient Greeks typically unstepped the mast and left it ashore. Sails are tricky to mess around with, they’re heavy, they’re cumbersome, they require men to be stationed aloft to work them (men who might be better used on the deck fighting). Not to mention, as Florent says, they’re a huge fire hazard. Not something you want fully extended when you’re sailing into range of wildfire.

By contrast, oars are not cumbersome, they allow for quick response time, and maximum maneuverability. Exactly what you DO want when sailing into battle.

If I recall from the chapter, they had the wind and chose not to use it.

I can’t comment on whether or not they had the wind, as I don’t have a copy of Clash anymore.

Regardless, my point still stands. It is common practice to take in the sails when going into battle, for any number of good reasons. Yes, they sacrifice pure straight ahead speed, but oars provide more than enough speed for ramming, which is all you really need. As well, a ship relying solely upon oars has the capacity to turn on a dime, or very nearly so. And in cramped waters such as these, maneuverability is far more important than speed.

Not to mention, Imry Florent was absolutely correct on the fire hazard of sails; witness what happens to Swordfish.

When they first encounter Tyrion’s navy, Davos notes that they’ve positioned themselves to avoid being flanked. And even if scouts could somehow get around the first line of ships, what good would that do? The wildfire is hidden inside the second wave, and wouldn’t be triggered unless the scouts attacked them, which is not what scouting is for.

Precisely.

Another thing I forgot to mention, and that I don’t think Steven takes into account here, is how Florent is essentially the equivalent of a corps commander. He’s been given charge of a large portion of the forces Stannis has, but he is still obligated to follow Stannis’s orders.

Here, Florent is following a plan that was laid out to him before he departed Storm’s End. Secure the river, wipe it clean of defenders, and make it safe for the ferries to begin to come over after that is done.

For Florent to deviate from this, such as by sending in scouts, ferrying the army to the north bank, or any other delay, would require the direct approval of Stannis Baratheon.

In order to gain that approval, he has to stop the entire fleet, send a boat to shore, find Stannis, discuss the plans with him, and then go back out to Fury. And if Stannis thinks Florent is wasting his time, he’ll be given the mother of all asschewings at best, replaced on the spot at worst.

And why would he risk that? When the fleet arrives at KL, nothing is out of place. Nothing, save the odd little towers on the banks. The wildfire ships are concealed behind the warships, and they were expecting the warships. Stannis is where he should be, the city is as it should be.

The winch towers are odd, but if they pose a threat, why would Stannis not have dealt with them? He’s been there for days now. Either they never posed a threat, or Stannis has taken them already. Either way, one of the top 3 commanders in Westeros has responsibility for that, and Imry Florent trusts in his commander to have taken care of business on the south bank.

It sounds like excessive management to demand that a commander acting not in direct communication with his superior refrain from something as basic as scouting the area he’s supposed to attack, especially in a time period before rapid communication.

Both Sean and I have explained why scouting sounds nice but is both extremely impractical and utterly pointless here. TLDR, any scout ships would either see nothing out of the ordinary, or get sunk before they could report all the small craft hiding behind the warships. And even if they saw the hulks and small craft, they still don’t know they have wildfire aboard, unless they have X-ray vision.

Again, it cannot be repeated often enough: When the fleet arrives, nothing is out of place. Everything seems to be as it should be, so why delay for no purpose?

I wouldn’t imagine they would guess at the purpose of the smaller vessels, but they could certainly report that for some strange reason the ship that should be the center of the defense isn’t there, possibly the conditions of the shore and the the chain.

The conditions of the shore? Who cares what the conditions of the shore are? As long as it’s there and solid enough to land troops on, that’s all the conditions you need.

The absence of King Robert’s Hammer is weird, but it doesn’t mean anything by itself. Certainly it doesn’t suggest a gigantic trap dangerous enough to deviate from the plan.

As for the winch towers, again, if they were any danger, then Stannis would have neutralized them. He also would have had the opportunity to scout along the bank and see the small craft for himself. If he had seen anything major, he would have signaled to Florent that the plan needed to change. He didn’t, so Florent assumes everything is fine.

Places to land? And remember that this all taking place with an enemy that has known for a while that the fleet was coming and had time to prepare. And the attacking fleet is aware of both of those facts as well. I would think that checking the situation would just be common sense. True the absence of the Hammer might mean good fortune like the Lannisters taking it to flee the city, but it could mean something else.

Now, would it have saved them? Maybe not since they couldn’t have known what was going to happen with the wildfire. But they should have known that this was weird and with such an advantage of numbers it wouldn’t cost them anything to scout, at least without the presentism of knowing that every minute would count because the Tyrells were on the move.

Again, you’re forgetting that Stannis has already been there with the army for several days. He can see everything. He can see the Lannister ships, he can see the opposite bank. ALL THE SCOUTING HAS ALREADY BEEN DONE BY THE ARMY, and Imry Florent knows this. And he knows that if anything was wrong enough that it required scouts, Stannis would have signaled him and changed the plan.

And if Stannis hasn’t bothered to send horsemen upstream, then that’s on him.

Wouldn’t this be the same Stannis whose forces have been dealing with a guerrilla war that blinded them to the Tyrell advance? And scouts who, if they did check the area, either missed or failed to communicate that Robert’s Hammer was gone?

And Florent knows this how? As far as he knows, the army has had zero trouble. Stannis does not communicate to him at all, and as the overall commander that is Stannis’s responsibility.

Let’s recap what Imry Florent KNOWS when the navy arrives at KL:

He was ordered to clear the river.

Stannis has arrived and has been there for several days, with a clear view of the Lannister fleet.

Stannis has the ability to light a beacon and summon him to shore to confer if he wishes.

He has not done so.

Therefore, there must be nothing seriously wrong that would require a change of plans.

Since the plan has not changed, he is obliged to carry out the plan.

This seems to argue both that it’s Stannis’ job to have scouting done and that Florent shouldn’t be at all concerned when he isn’t getting any information from Stannis.

That is exactly what I’m saying. Stannis is first, the supreme commander. EVERYTHING is ultimately his responsibility. Secondly, Stannis has been on the scene longer and therefore should have a grasp of what is going on.

Why should Florent be concerned that he isn’t getting info? There isn’t anything that would be preventing Stannis from communicating. Stannis isn’t under attack that he can see.

There is simply no cause for concern. None. At all.

I take the opposite view. Going on the basis of there should be, so far as Florent knows, nothing stopping Stannis from contacting him and that Florent is a major commander in charge of a vital part of the plan in an upcoming battle, I’d think Florent should find it very strange that Stannis wasn’t contacting him if complete responsibility for scouting fell on Stannis’ force. Shouldn’t the main commanders discuss any developments or lack thereof before starting the battle that could very easily decide the entire war?

But there are no developments. That is the logical conclusion. If Stannis has nothing stopping him from contacting Florent and has not done it, then the logical conclusion is that there is no reason for Stannis to do so. Since Stannis is not flagging him down and telling him to change the plan, then he naturally assumes the plan has not changed. Simple.

I am sorry but that just says to me that Florent is being overconfident and making assumptions of all being well even though he should know what the stakes are. It’s probably the most important battle of Florent’s career, one that can firmly put his lord on the throne and knock one of the major players effectively out of the war, and he doesn’t have contact with the ground forces? Apparently that means to him to just go off without a second thought.

In all seriousness, they weren’t even in contact to set the time for the attack? And if they were, then Stannis should have made the limitations clear to Florent.

Why would he get in contact with him just to tell him the plan hasn’t changed?

Stannis’ orders were for speed. He’s there, and he implements the plan. Simple and straightforward, nor is there any reason to think Stannis would have ordered him to do anything else. Stannis clearly wasn’t concerned about the tower, else he would have dealt with it (indeed, what was Florent to do about that?); nor did he have any idea about the wildfire, or find the enemy dispositions suspicious enough to flag Florent.

Nobody had any idea about the extent of the wildfire, nor could they have. Without that knowledge, all of his decisions are sensible (and effective, for that matter).

Because, as we clearly see even discounting wildfire (which I’ve already agreed couldn’t have been predicted) events on the ground change. Only Florent apparently couldn’t get that. He went in there assuming that nothing had changed and all was well. Compare this to Jaime after he has command of men again. His order after he leaves King’s Landing? Start scouting out and keeping careful watch, even in an area he knows is as safe as it can get.

If we want to judge Florent for his battle plan, we need to know what Stannis told him. Considering the fleet held a war council while sailing to Kings Landing, the orders weren’t that precise. He could have made changes. Scouting the river, like Davos suggested, could have meant, sail in, have a look, maybe lure them out. It doesn’t have to mean, pass the ships and look what’s in the back.

Sailing headlong into the river is like a class of 10 year old running the escalator in the wrong direction. It only needs one big old lady/sir to ….

That’s Steven’s point: You give up your greater numbers (like Cannae or Salamis), even without the (extra) wildfire and the chain it would give the Lannisters a chance to destroy the fleet. Once the ships are stuck, they can’t use their oars, the next ships will push from the back, none is able to navigate.

And why put the ships with soldiers you need to land and scale the walls in front? If the Lysenii do the job, they are the better sailors, you don’t need them to take the city and you wouldn’t have to pay them if the plan fails (Jaime at Riverrun).

GRRM wanted the chain and the wildfire, therefore he made the southern tower untakeable, he made the storm and he made Florent like Florent: A lord, who has no experience in naval battles, but is to dumb/proud to counsel experienced naval commanders under his rank.

I think, even if you have orders, if you have the greater numbers, if you are in a hurry it’s a always a bad choice to jump in a black hole without checking it out first.

Gosh. It seems you’re writing faster than I can read. What’s your secret ?

I’ve been writing non-stop (and listening to Non-Stop) pretty much since the Kickstarter ended. So I guess the secret is motivation and underemployment?

1. “Off Merling Rock two days before, they had sighted a half-dozen fishing skiffs. The fisherfolk had fled before them, but one by one they had been overtaken and boarded. ‘A small spoon of victory is just the thing to settle the stomach before battle,’ Ser Imry had declared happily. ‘It makes the men hungry for a larger helping.'”

Can I point out the pointlessness and lack of necessity in attacking unarmed fishing boats?

2. The Swordfish is the naval equivalent to the Little Pigeon’s Herons with their stilts.

3. “Queen Alysanne and Lady of Silk, still locked together, were a raging green inferno, drifting downriver and dragging pieces of Lady’s Shame.”

Foreshadowing for Cersei, with Queen Alysanne being a metaphor for Cersei? As for Lady’s Silk, the Street of Silk is named for its brothels, and this is a point to Cersei exchanging services from men for sexual favors. Lady’s Shame pointing to her walk of shame, and “a raging green inferno, drifting downriver” points to Cersei’s growing madness, akin to wildfire which Aerys was fond of.

“Directly ahead, Davos saw the enemy’s Kingslander drive between Faithful and Sceptre. ”

The sceptre is a king’s object. Does this foreshadow the struggle between the Faith and the monarchy in King’s Landing?

Can be justified by wanting to get information on conditions, but is certainly nothing to gloat over.

But from the sound of it, only Davos was insterested in what they had to say while Imry didn’t.

Except that, as we learn in Storm, Varys loves using fishing boats to spy on Stannis.

These fishermen/spies won’t get back to report, at the least.

Except those fishermen who were spies were at Dragonstone. These fisherman are local in the waters not knowing the fleet was headed there, and what would they need to report? What is the need for secrecy in this instance given KL already knows Stannis is going to assault the city and the fleet is on its way?

They were in the waters around Dragonstone. Not at Dragonstone itself, obviously.

What would they need to report? Um, that the fleet has arrived? Tyrion knows it’s coming, but there is great value in the information that it’s coming now, as opposed to next week or next month.

Next month? If Tyrion already knows the fleet is coming, and storms are delaying them, then what more info would he need? Stannis’s army is already approaching the city through the kingswood, and that means the fleet is likely not far behind.

The point is valid. Knowing that the fleet is going to arrive within, say, the day instead of three really is the sort of detail that matters at Blackwater. Plus if a fishermen closer to King’s Landing had noticed that there was some long chain being put up and had mentioned this, it could have made the difference if the admiral had listened.

*Of course trying to catch every boat along the way to keep news of your movements secret is probably going to be impossible.

Except the warships in the fleet are much faster than small fishing boats. The fleet will reach KL long before the fishing boats do as well as anything by land where the boats dock given travel by sea is faster than by land.

They aren’t necessarily faster than a route of ravens though.

Except Varys doesn’t use ravens.

Thank you Steve not only for this brilliant analysis but also for telling us about Reg.

Not knowing jack about naval tactics I’m afraid I can’t contribute much here except to note that showing the rank and file’s viewpoint of the carnage on the Blackwater was a master stroke.

My pleasure! It’s a story I’ve wanted to tell since I was a kid.

I second winnief’s comments regarding Reg. I don’t know how long he lived, or if indeed he is still living, but I hope that you got to hear some of those stories first hand. I remember late in my grandfather’s life when I was about 16 and we were visiting him over Christmas that I realized that the stories of his day to life that he always told were really fascinating and I wished I hadn’t been a stupid boy and had been listening to him all along.

As a sidenote, I’m basd at it and I might have just seen it because I was looking for it, but I think I detect a family resemblance from that photo to you.

Reg looks quite a bit like a young Ben Gazzara. Thank you for sharing his story, it’s truly remarkable.

Warships can sail up the Blackwater twenty abreast. How wide does that make the Blackwater? Or in other words, how wide a passage does an oared ship, with oars outstretched on either side, need in order to avoid fouling obstacles on either side? Does anyone know?

Mental typo, I think?

As for the rest, your grandfather’s mustache alone meant that he would survive. A man with a mustache that amazing cannot die by ordinary means. Damn!

Mental typo indeed.

You wrote that Stannis’s navy is faster than army at one point, when it should be slower.

You are really spoiling us with these chapters, maybe I should stop reading them and save them for later when the chapters are not coming this fast.

Will fix.

Very moving story, thank you! Love the analysis too, can’t wait for Davos in ASOS–one of my favorite arcs for sure.

I do wonder why the Tyrion never equipped his small fleet of warships with wildfire like the Byzantines did? They do have the technology to siphon wildfire as proven from Aegon IV’s wooden dragons, I would have thought if Tyrion revived the old plans for these crude flame throwers he would of had a huge advantage over Stannis’s navy.

I don’t think they’ve refined that technology to the point of reliability.

Remember, the wooden dragons exploded in the kingswood, hardly making it any distance at all.

Not to mention that those wooden dragons killed 100s of its support crew.

You’re my hero. Steve! Thanks for the phenomenal analysis!!!

Re: the book to show section: how do you feel about the show amalgamating all of Davos’s sons into one? On the one hand, it hits harder when he dies, because they’ve established a bit of a relationship throughout season 2, but on the other hand, I think it changes Davos’s story a bit later on if he has no sons left. In ADWD there was always the thought that he might return to his little island with his boys and his wife, but without that anchor he seems a bit lost in later seasons.

I know this is a bit of a small change, but it always irked me a little, so I’m curious what you think.

Seems to me that they could have said that the other sons exist, have just the one interact with Davos so that when he dies we really understand the sense of a father losing his son and mention after Blackwater that there’s just one left.

His story really is one of those nice parts that brings home the costs the war has had and the costs of his loyalty to Stannis. His knighthood bought his family far more success than they could have hoped for, but it’s also led to almost all of his sons dying in a war that they might have never been part of if Davos hadn’t been knighted.

We all came out to King’s Landing

On the Crownlands shoreline

To make war with a boy king

We have lost much time

Imry Florent and Maric

Were at the best ship around

But some stupid with wildfire

Burned the fleet down

Smoke on the water, fire in the sky

Smoke on the water

(sorry, couldn’t resist. Great write-up!)